The Summit Series

Follow Me on Twitter, LinkedIn

View Count: 219

A few years ago I was sitting in my office when I got call from a guy named Elliot Bisnow. Mr. Bisnow told me about a conference that many important people would be attending.

“We stand for the New Generation!” he told me. The people who’d be attending would all be “new influencers,” and no one at the conference (aside from the speakers) would be over 40.

Mr. Bisnow was engaging (we talked tennis) and enthusiastic, and I was intrigued with what sounded like a loosely defined social movement of young people. Wanting to learn more, I probed him about his beliefs and the tenets of the group he represented, but I did not get any solid information. He told me that all the speakers had agreed to speak for free because they’d be addressing the new generation and new influencers.

“Wow, this sounds like an interesting conference, Elliot,” I said. “That’s great that all these speakers are appearing for free.”

Then Elliot asked me for $3,500. He said that’s what it would cost to attend his conference, and repeated that hundreds of young people would be there.

It suddenly became clear to me that this conference had more to do with Elliot making a lot of money than any kind of new generation. I quickly lost interest.

Over the next week, Elliot called me at least five times—always bubbling with enthusiasm. He emailed me a PayPal account to which I could send the $3,500. He sent wire instructions. The calls just kept coming. Elliot really wanted my money. I‘d never been marketed to quite so aggressively for a seminar at which everyone would be speaking for free. Elliot was going to make a killing.

I figured the only “new generation” people who’d be going to his conference would be kids whose parents had a lot of money—or who were now making a lot of money themselves as businesspeople, doctors, lawyers, and so forth (people unlike Elliot).

I largely forgot about Elliot until several months ago. I was living in Malibu next to a giant 12-bedroom house that had been on and off the market for $40 million. The owner (a Holocaust survivor) was in his 80s and wanted to sell the house. But the house, which he’d built more than 40 years before, was severely outdated and not the sort that people with that kind of money would be interested in buying. Moreover, the owner faced massive capital gains taxes if he sold it. So his plan was to lease the house out for a few years and then sell it as a business investment.

He initially asked for $30,000 a month. No takers. The house languished on the market for months, until one day a few moving vans drew up. It looked like it had finally been rented.

The next Saturday a scruffy-looking fellow knocked on my door. He had long hair, as did the sketchy-looking friend who was with him.

“Hi! I’m one of your new neighbors!” he announced.

As we chatted he explained how he was part of a “new generation” company in which everyone lived and worked together. He figured 14 people would soon be living and working together in the house next door.

My house was on the ocean.

“Do you surf, man?” the first guy asked me.

“No.” I replied.

They asked if I had an extension cord they could string into the house to power their cell phones. The owner had apparently turned off the power when he’d rented them the house. So I lent them an extension cord.

Over the next several days, more people moved in. Old Jetta cars pulled into the driveway at all hours. Conversations could be heard outside their house morning and night.

Unfortunately, my house and theirs shared a driveway, so the cars that came down the driveway at all hours were particularly intrusive.

A few days after I lent them the extension cord, the guy who’d borrowed it came to return it. He thanked me and invited my family over to dinner.

“We have our own chef,” he bragged. I chatted a bit with him about the “new generation” group next door. He told me they made a lot of money putting on seminars and had just finished one on a cruise ship. He said they were a “think tank” that “did very well.”

Think tank. That was something I would hear from a number of people living in the house next door over the following weeks. Now, traditionally I’ve expected people associated with think tanks to be Ivy League PhD types—or at the very least, intelligent academics. From what I saw, however, these think-tankers were image-conscious kids with questionable academic pedigrees.

“Thanks for leasing out the house next door to 15 kids!” I emailed their real estate agent a day or two later.

“It’s a 12-bedroom house,” he replied. “They’re an organization called the Summit Series and have lots of important speakers.”

I looked up the Summit Series online. I should have known: It was run by Elliot Bisnow.

I called the City of Malibu to speak with Building and Safety. At least 15 kids in their late 20s and early 30s were living next to me. Was this legal?

“If you tell me where it is, we’ll probably shut it down. Regardless of the number of bedrooms, it’s a single-family home. There’s no way that’s permissible.”

I considered “narc’ing” on my new neighbors but backed out in the end. Instead, I fired off an email to the realtor about the illegal living arrangements next door.

A few weeks later my gardener told me at least 25 people were now living there. They’d put more than one bed in each bedroom. Their gardener had clued him in.

My house had its own private cove on the beach; it was large and had incredible views. The house the kids were living in had an easement down to the beach—meaning they could walk down a path to get to the beach, but it was not their property.

Soon the kids took to standing in my backyard (our property had a gate to theirs) and populating the cove. I warned them off standing in the backyard. “Sorry, dude,” they’d say and prance off. Some of them seemed a little intimidating. One of them had a Mohawk and looked like Mr. T.

One Saturday I came home and couldn’t get in my driveway. There must have been 400 people at the party next door.

“We’re going to have at least one party a month!” one of the kids told my wife.

I was in my kitchen playing with my daughter when I looked next door and watched in astonishment as a man took some cocaine out of a small vial and snorted it with a girl. When they noticed me looking on they laughed.

I called the owner on Monday morning.

“What do you want me to do about it?” he said.

Why I didn’t report the kids right then and there? I’m not sure. But it was becoming obvious that this was more a 24/7 party than a “think tank.”

The parties continued almost every night. My driveway was constantly blocked. Along with the noise were steady intrusions into my backyard.

My wife talked to a few of them. “They seem like image-conscious kids with wealthy parents. They’re not that smart and are using this ‘new generation’ and think-tank stuff to get money,” she opined.

During one party, and despite previous warnings, Elliot and about 25 of his friends were hanging out on our cove. One guest was taking a leak in the bushes while another ripped branches off one of my trees and chased a girl around with them, swatting at her butt.

“I don’t know what the hell you people think you are doing, but this needs to stop,” I told one of them.

“Excuse me, who are you?” Elliot asked me with cool detachment.

“I’m surprised you don’t remember me. You cold-called me five times about your seminar, asking for $3,500. Listen: you’re living illegally next door. You’re pissing on my lawn. You’re ripping branches off my trees. You’re loud. I don’t know who you think you are, but this absolutely needs to stop.”

Things didn’t get better from there — they got worse. One Sunday night I was awakened at 11:30 by drunk people singing ’70s rock ballads. Cars came and went. Doors opened and slammed shut every few minutes.

The tenants began parking up the street when they ran out of spaces. The parties continued.

Then their septic tank started to overflow. Human waste came down in a small stream aimed at my house. It took days to fix.

And every few nights people would knock on my front door, waking my children, looking for the party. But since we shared a driveway, there was little I could do.

One evening I came home to a multitude of signs that had been posted all over my property, reading PARK ON THE STREET –- LOVE, ELLIOT

I threw them back onto their property.

The next day a young girl appeared at my front door in search of the signs. She was an attractive recent graduate of USC and part of the movement next door.

I asked her some questions about what the organization stood for, and her answers were predictably vague. I told her I didn’t appreciate the drug use or loud parties next door. She handled herself professionally.

“What should we do? Our business model requires everyone to work together in a house,” she said.

I could not imagine why people in their 30s would want to share a house and bedroom with 25-plus coworkers.

“Why don’t you all get an office and then apartments?” I suggested.

My assistant, who’s very smart, was standing next to me: “I bet they don’t pay you, do they?” she said. The girl looked surprised. My assistant’s theory was that for all the talk about the “new generation” and “new way of working,” what was really going on was this:

- Young people were given “jobs” that allowed them to work in nice locations.

- They were paid very little if at all.

- People worked on seminars where they looked for people to speak for free to the “new generation.”

- They didn’t care about not being paid much because they were fed and given places to stay.

- They felt important because they were part of a “think tank,” lived in nice locations, and were sheltered from the stresses of the real world.

- Elliot the Guru held seminars and made a lot of money and got to feel important.

It had all the earmarks of a cult.

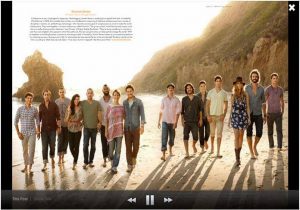

For all this, I think the most shocking part of my summer had come earlier, when I’d opened a Vanity Fair magazine and saw a picture of some of the Summit Series kids standing on the beach in front of my house. It was a two-page photo spread — an article, I assumed, about them and how influential they were. But then I looked at the upper right-hand corner and saw the words “Special Advertising Section.”

Some of the Summit Series people must have believed this was a special Vanity Fair editorial piece on the important work the group was doing and their concerns about shark tagging and the like, because when I found this image online (I threw away the magazine) a Summit Series member had posted: “Thanks to all at Vanity Fair who made this possible … we are humbled and grateful.”

I recalled this as I now spoke to the girl. “What kind of organization takes out a two-page spread about itself in Vanity Fair?” I asked her. “If you’re so concerned about these causes, why spend $75,000 to $100,000 for an ad promoting your image? Why not use the money to send people to seminars to help with shark tagging?”

The girl had no answer except “That’s how they chose to write about us.”

Four years before, I’d entered into an option agreement to buy the house I was in, and I’d invested a lot of money in it; but all the money I’d invested was now basically gone, because the market had crashed and wiped out my equity. It was up to me whether to stay in the house or leave; I just had to let the financing company know one way or the other by September.

With all the chaos next door, I chose to leave. The situation had become intolerable, and there seemed no solution. Had the Summit Series not been next door, I never would have moved. But we were desperate for a quieter neighborhood and some privacy.

In many respects, I feel sorry for the 25-plus people living there next door to me. They are indeed the “new generation” in many respects, and I think they’re probably seeking the same sense of importance we all crave. They’re part of a bad job market that offers few opportunities, and the Summit Series has provided them a way to feel they’re contributing something positive to the world, whether or not they actually are.

- They take out advertisements promoting themselves so they can feel important.

- They use “think tank” very loosely to make themselves sound intelligent.

And there’s definitely something cultish about what they’re doing. They have an enthusiastic founder who preaches in broad strokes. They’re all living together, eating together, and probably not being paid much. There’s nothing “new generation” about this whatsoever: This is what cults have done forever. David Koresh and the Branch Davidians in Waco did it, the People’s Temple in Jonestown led by Jim Jones did it, the Heaven’s Gate cult did it, Charles Manson and his followers did it, religious figures in the past have done it. In fact, having a bunch of low-paid followers living with you and going out and making money for you is about the oldest business model there is.

It’s simple: You get people with low self-esteem and make them feel they’re part of something important. You take care of them by housing and feeding them. You make them dependent on you. Giving people a place to live in Malibu, hiring a chef, taking out ads in Vanity Fair—the methodology is formulaic for cults and similar organizations.

I’m not sure how easy it will be for the Summit Series people to get jobs after their time with the organization. What I do know is that they’re part of something that‘s positioned as a positive organization with good intentions. But again, that’s what every cult does.

The biggest lesson I’ve taken from my association with the Summit Series people is the importance of values. I know how my family was treated living next door to them. I look at their actions and see people with a complete disregard for anyone else’s property, privacy, or family, as well as disregard for the law.

The Summit Series values, such as they are, are bogus. From what I witnessed and experienced, the organization cares very little about those around it and is purely out for itself.

In any organization you’re part of, it’s critical to understand what its values are and whether those values are supported and acted on. Are those values consistent with what the organization says it stands for? Does the organization really mean what it says—or does it just pay lip service to what’s convenient and convincing?

When you’re looking for a job, consider how the organization treats others. If an organization is capable of harming others, the odds are pretty good it’s also capable of harming you as well—and will do so if it serves them.

Several years ago I referred a good friend to an attorney I know who presented himself as religious, a hard worker, a stand-up person. I was won over by his talk of ethics and doing the right thing.

But the attorney took advantage of my friend and overbilled him badly. I thought about this and moved on. Then sometime later I brought some legal work to that same attorney — and he did a similar thing to me too. He billed me tens of thousands of dollars for work I had not asked for.

In the end, you can learn a lot from observing people’s actions—which we all know speak louder than words. If someone is dishonest or disrespectful or shows bad values with one person, it’s likely the same thing will happen to you if you choose to take your business there.

The converse is also true: You must act with integrity or bear the consequences. If you’re doing business with people who’ve been around the block and have experience, they’ll back off instantly if they see any incongruity between what you say you stand for and what you actually do. This is especially true with the more successful businesspeople out there. The moment something does not seem consistent, they won’t deal with you. Ever.

You generally can tell everything you need to know about a person’s or organization’s values based on their actions—because in every case, actions show values. Don’t forget it. Because other people surely won’t.

About Harrison Barnes

Harrison Barnes is the Founder of BCG Attorney Search and a successful legal recruiter himself. Harrison is extremely committed to and passionate about the profession of legal placement. His firm BCG Attorney Search has placed thousands of attorneys. BCG Attorney Search works with attorneys to dramatically improve their careers by leaving no stone unturned in a search and bringing out the very best in them. Harrison has placed the leaders of the nation’s top law firms, and countless associates who have gone on to lead the nation’s top law firms. There are very few firms Harrison has not made placements with. Harrison’s writings about attorney careers and placements attract millions of reads each year. He coaches and consults with law firms about how to dramatically improve their recruiting and retention efforts. His company LawCrossing has been ranked on the Inc. 500 twice. For more information, please visit Harrison Barnes’ bio.

About BCG Attorney Search

BCG Attorney Search matches attorneys and law firms with unparalleled expertise and drive that gets results. Known globally for its success in locating and placing attorneys in law firms of all sizes, BCG Attorney Search has placed thousands of attorneys in law firms in thousands of different law firms around the country. Unlike other legal placement firms, BCG Attorney Search brings massive resources of over 150 employees to its placement efforts locating positions and opportunities that its competitors simply cannot. Every legal recruiter at BCG Attorney Search is a former successful attorney who attended a top law school, worked in top law firms and brought massive drive and commitment to their work. BCG Attorney Search legal recruiters take your legal career seriously and understand attorneys. For more information, please visit www.BCGSearch.com.

Speak Your Mind

Tell us what you're thinking...

and oh, if you want a pic to show with your comment, go get a gravatar!

Comments

6 Responses to “ The Summit Series”Filed Under : Featured, Life Lessons

Tagged:

recent posts

Related Posts:

Dear Mr. Barnes,

Several months ago I read an article on the Summit Series and their plans to create an entrepreneurship village in Utah. The whole idea seemed very intriguing so I began doing some research on the organization. I got no further than their website’s “about us” page before skepticism started to take over. The images and bios of their members caused a sickening feeling in my stomach. No diversity in the larger sense of the word, while I’m sure they would claim maximum diversity because one member is a yoga expert while another is a tennis player… I reached out to several of my friends to ask their opinion and to stress mine, that this was more cult than company. A rather wealthy friend of mine currently in Hong Kong wrote back, “i see where you’re coming from, but aren’t we also this type of person?” Her response troubled me and I soon forgot about the Summit Series after just an hour or two of research.

I am uncertain what sparked a reminder today but I decided it was necessary to revisit the subject, and eventually I stumbled across your post on your experience with them in California. After reading this I could honestly say, “this is not me”, “this is not us”, and “this is not okay”. While just 23 years old, I am lumped into the “young professional” group, the same group as you and the same group as these Summit Series fellows. What rich 30 somethings want to do with their life is their business, just as you initially turned a blind-eye to their residence next door and accepted them as fellow human beings just enjoying their time on the beach and working. Soon they began to threaten your personal life and that of your family, which is unacceptable.

After continued research I feel that the same threat is being made to my entire generation. These people, their founders, and their members have been elevated to a level that allows them to be speakers for our generation. These are the people who are supposed to represent me, supposed to represent the future. They are the urban chic, the “rich kids of instagram” , and the heir to the much lamented 1%. All of this you undoubtedly know but I would like your input on the danger being posed by this organization. The ability to shape legislation based on one shared opinion instead of the opinion of the entire population. I am worried mainly that the draw towards this type of organization is extremely luring. I myself am almost tempted to take part, what is not to love with a nomadic lifestyle, traveling the world, and using your influence on others to play rich. I am terrified that this group is so well orchestrated it may go far beyond the Summit Series and lead to a further gap between rich and poor. Do we have to allow this? With such a strong following and members from the leadership of Twitter, Facebook, Trump etc. do we have a choice? While their intentions may not affect you or I personally, do we not have a moral obligation to defend and speak for those who are not given a voice in these matters? The 99+% who aren’t “Summit Material”? Would love to hear your opinion.

All the best,

Mike

Michael.

I really enjoyed your email and think it offers a tremendous level of insight. What concerned me the most about the group from a “holistic” point of view is that they are really creating a “mirage” of influence in order to earn money and “play rich” as you mention. Something else I would mention that I find very interesting: By having people work for basically free on a profit-making enterprise they are likely not paying payroll taxes and so forth. This is not contributing to society on its most basic level – even McDonald’s helps society with payroll taxes.

–Harrison

It is definitely part of disheartening trend of those who have separating themselves from those that do not. I am almost less concerned that their “employees” aren’t being paid as I doubt they care if they are being given everything they want. I also believe that Bisnow is not doing it for the money but more for the power of influence. He seems to be able to convince his rich friends to bankroll whatever it is he likes. They recently purchased Powder Mountain in Utah for $40 million to build a community. It is an eerily similar idea to Glenn Beck’s Independence USA plan. The difference is our president and politicians are actually turning to Bisnow for policy advice. It would definitely make for a very good investigative journalism piece.

-Mike

Thanks for your post. The Summit Series is currently occupying a home in my quiet home town in Utah, causing a slew of unpleasantness and blatantly violating zoning laws. This is occurring just down the street from our elementary school, which is concerning. It was helpful to hear your experience.

Why didn’t you burn down the house with them inside it? I’m sure your family and others neighbors would have celebrated.

Call me bro!